Until a couple of decades back, Indian politicians were restricted to using only Indian cars, the now extinct Ambassador or Premier Padmini. The cars of the President and the Prime Minister, however, except for the facade, contained engines and other mechanisms imported from Germany, etc. Both companies have since gone the way of the dodo, for they failed to innovate, and had very significant quality issues. While they existed, Indian roads were ridden with broken-down cars.

There is nothing wrong with imported cars, but one must ask why a nation of 1.35 billion, representing one out of every six human beings on the planet, has no car-brand of its own. In fact, it is hard to think of a product that India excels in.

Indians have always had a fascination for goods manufactured in other countries. Before the relaxation of imports in the early 1990s, starved of quality and mostly even to access, goods imprinted with a false foreign country of origin could be sold for a multiple of the actual price.

Indians buy foreign-made products not just for quality, but also as status symbols. Indians like the tag of a foreign university, even if such a university is “run” from a residential apartment in a well-known city in the West.

Most politicians and bureaucrats want their children to study at a prestigious university in the UK or the USA. Some even send their teenage kids to finishing schools in Switzerland, the UK or Canada. I can hardly think of any of those that I wined and dined during my days in Delhi who did not send his children abroad.

While Indians today claim to be very proud of being Indian, given an opportunity most would sell their kidneys or more in exchange for opportunities abroad. Most would rather own foreign brands than support Indian businesses. There is indeed nothing wrong with either buying foreign-made products or trying to emigrate, for we all want the best for ourselves and our families. There is, however, something very demeaning, degrading, and spineless about being hypocritical, about saying one thing and doing the exact opposite, about claiming to be the best country in the world while using foreign-brands as status symbols.

India’s love for everything foreign also has a rational basis.

India makes extremely shoddy products, with noncompetitive costs. The end result is that even very simple plastic-toys manufactured in China (whose workers get an as much as five times the salary compared to India on a like-to-like basis), which must be transported thousands of miles on bad roads to India while paying bribes all the way, end up being cheaper and of higher quality when sold in stores even in remote Indian villages.

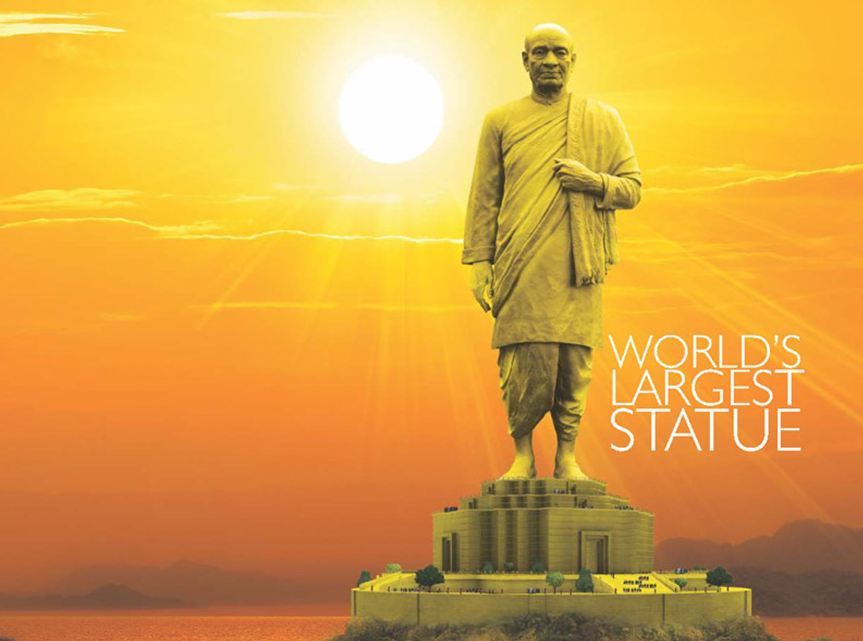

India is constructing a 182-meter high statue of Vallabhbhai Patel at an island near Vadodara. The estimated cost is INR 2,989 crores (approximately, US$299 million). Depending on your inclinations, you might cringe about the forcible expropriation of land and the costs involved, in a country where at least 250 million people go to bed hungry, or feel proud that India will soon have the tallest statue in the world. In case you feel the latter, you will need to numb yourself to a crucial fact that the key parts of the construction work is being done by Chinese workers and companies.

Despite his personal interests in imported luxury items—pens, watch and glasses—Prime Minister Modi has advocated “Make in India” as a slogan. Unfortunately, slogans have no value in real life. If India has to “Make in India,” it must improve its quality and cost structure.

Modi recently used a US-registered seaplane (ultimately owned by a Japanese Shipping company) in the just concluded Gujarat assembly election campaign. One might understand that India still cannot make its own fighter planes (despite having spent a fortune and decades on development work) or even seaplanes (which are rather simple in design). But does Indian navy or coast guard not have a single seaplane with an experienced pilot?

We maximize utility through division of labor. Importing what we need and want is a necessary part of this game. We can understand that India might have to continue to import luxury cars and seaplanes into the foreseeable future, but there is no reason why given its huge unemployment and cheap labour, India’s foundry products or toys are noncompetitive. It is indeed hard to explain why India seems not to have trustworthy seaplanes—not even one—even with its navy or the coast guard.

We maximize utility through division of labor. Importing what we need and want is a necessary part of this game. We can understand that India might have to continue to import luxury cars and seaplanes into the foreseeable future, but there is no reason why given its huge unemployment and cheap labour, India’s foundry products or toys are noncompetitive. It is indeed hard to explain why India seems not to have trustworthy seaplanes—not even one—even with its navy or the coast guard.

Yes, India needs “Make in India”, but not just the slogan. It must walk its talk. It must create a skilled, trained workforce. It must focus on quality. It must improve its cost structure, and reduce leakages and wastage.

The author’s observations are so very acute. After visiting 50+ countries, the common theme I’ve noticed about Indian products being sold abroad is – there are almost zero Indian products being sold abroad.

Apart from food items, eg. Haldirams, the other products labelled “Made in India” are usually jute rope, pottery items and handmade fabric bags. There seems to be limited capability to work with industrial materials in India. On the other hand, Chinese made products are everywhere. There seems to be nothing that is beyond their ability to manufacture. The news that the statue in Vadodara is being made by Chinese just confirms this.

The author’s observations about ” goods imprinted with a false foreign country of origin could be sold for a multiple of the actual price” is also so very true. I know a shop owner in Delhi who sold transistor radios, walkman sets, etc. He would recruit foreign tourists to pose as if the radio was theirs and thereby sell it for 3x the usual price.